Your donation will support the student journalists of Grand Center Arts Academy. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

PHOTO ILLUSTRATION: Many people will post pictures of symmetrical, color-coded, or neatly arranged objects and talk about how it soothes their OCD on social media.

I’m so OCD: It’s an illness, not an achievement

February 12, 2020

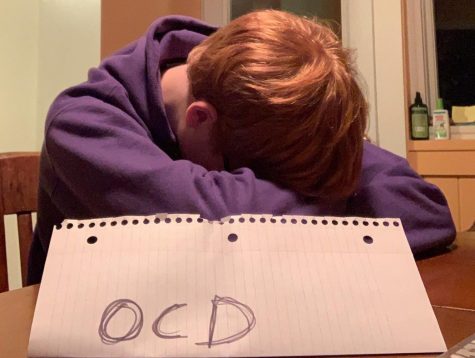

PHOTO ILLUSTRATION: OCD is a constant, exhausting struggle. Gabe Gibert illustrates the frustration felt when combating his OCD.

A short warning: this is potentially VERY triggering to anyone with OCD. If you’ve been diagnosed, proceed with caution, and keep in mind that this isn’t aimed at you anyway.

I am diagnosed with OCD. My backpack is fairly messy, as is my room. The pictures on my wall are always crooked, and my bookshelf is a complete disaster. I am not a neat freak by any definition. So now you might be wondering: “What gives? I thought you said you were OCD!”

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, or OCD, is a mental disorder characterized by two parts: first, intrusive thoughts which cause shame, guilt, anxiety, or other negative emotions, commonly known as obsessions. The second part, compulsions, are repetitive behaviors to attempt to soothe these obsessions, often highly ritualized in their nature. This is not “being a neat freak” — this is a chronic, debilitating pattern of anxiety and life-disrupting rituals.

Many people categorize OCD into subtypes or themes. An OCD person’s brain will find obsessions, but what those are specifically are unique to each person, though they run in a few common channels. If you spend your days washing your hands to scrub those germs out and constantly obsess over sickness, that would probably be contamination theme; if you’re constantly reminded of your impending mortality and insignificance, that might be an existentialist theme. A sufferer often will have multiple themes and can get a new one at basically any time. Intrusive thoughts aren’t limited to a theme, either; they will pick whatever you’re most anxious about and drill into it. The theme is just a fallback for anxiety.

Let’s walk through a particularly bad day with OCD. (For this example, I’ll show a really bad day, though not anything out of the realm of possibility, and I’ll jump around between themes to show the full scope.) You wake up, and you might have a few blissful seconds before you have an intrusive thought, or maybe your first thought will be the most horrible thing you can think of.

You get up and accidentally step on something, maybe a bit of food or something gross. Uh oh – contamination time. Will you die of some horrible disease stored in that little bit? Yes, your brain assures you, you will. And you will die horribly. Your brain is filled with images of diseased people, of decaying flesh, hospital gowns, and somber doctors. You know, logically, that you’re not going to die, but logic is thrown out the window by these obsessions.

Well, you’re going to die. What now? Well, there is a spark of hope: wash your hands. Do you feel clean? Of course not! Do it again, and again, and again, until your hands are chapped, and dry, and cracking. It helps, for the moment, but if you’ve had any therapy you’ll know that you’re actually pushing yourself further into the obsession and making it worse in the long-term, but of course it’s difficult to keep that in mind while in the grips of a compulsion.

PHOTO ILLUSTRATION: Some people feel the compulsion to wash their hands constantly, even until they bleed, to cope with intrusive thoughts surrounding contamination, disease, and sickness. Haile Emerson reenacts the compulsive tendency.

Crisis temporarily averted, though you still feel the dread hanging over you. How can you know if you’re actually clean? Your brain decides that you can probably fit a bit of obsessive rumination (dwelling on an event, replaying it and analyzing it to see what went wrong over and over) before breakfast. Time to think about that time you called your teacher by the wrong name and your class laughed at you. You get to replay it over, and over, and over. Did they think it was funny? Or did they think you were stupid?

You get in the car. Is there ice on the road and it’s just hard to see? I guess you’ll all die. You got a headache, it must be brain cancer. What if God is actually real and he’ll send you to hell for ever wondering? What if multiple gods are real and they’ll be angry if you believe in the one God? This requires further thought, and you don’t get a choice in the matter.

Does this example have you exhausted yet? I am. You haven’t even gotten to school yet and you’ve already faced death three times, or four if you count potential divine smiting. It seems ridiculous and comical from an outside perspective, but these thoughts cannot be escaped. You can’t get away from them, ever. You don’t really believe them, but you can’t make them go away. There is a constant mental assault on your conscious mind.

You’ve made it to school and you go to your first class. As you walk up the stairs, you see an image of yourself slipping and falling down the stairs, bones breaking and skull cracking open. There’s blood everywhere, and you can’t escape from the images. When you finally get to your class, you set your stuff down. You hear a conversation behind you: a girl in your class is showing off her planner to friends. “It’s color-coded!” They ooh and ah. “Yeah, I HAVE to have it neat,” she starts.

“I’m so OCD,” she says.

How do you feel right now? Angry? I probably would be. She’s OCD? Just because she has twenty thousand pens in all different colors and likes to clean her room every now and then? How dare she? Has she washed her hands until they bled? Has she stayed up until four in the morning, too ashamed of a tiny mistake she made six years ago to sleep? Has she spent hours just wishing for the intrusive thoughts to please, please just stop so she can catch her breath? You have.

The point of this is not to make you feel pity, and it’s not to make you feel bad if you’ve ever used this phrase. I know lots of people think OCD means neatness or clean freak, and it’s not their fault that they don’t know. The problem is that the use of OCD in this context trivializes it: it reduces it from a lifelong, debilitating condition to “just generally preferring that things be neat.” My mental illness is not a good thing. OCD is the worst thing that has ever happened to me. I don’t hate you if you’ve ever called yourself OCD, but please just think a little bit more before you claim a disease as one of your positive attributes and pay attention to how you would feel.

As a final note, some OCD sufferers really do need things to be straight and orderly. This is called the “Just Right” theme, and it is essentially the OCD stereotype: distress when they see objects that aren’t neat or arranged in a certain way, obsessive neatness, or feeling compelled to straighten paintings (this is not the full list, just a few samples). I am not trying to discount or invalidate their experiences and struggles, and they suffer just as much as anyone else with OCD, but their experiences are a far cry from seeing a bookshelf out of order and being mildly irritated.

If you think you have OCD, please speak to a therapist so you can potentially get diagnosed and get the help you deserve.

Resources:

St. Louis Behavioral Medicine Institute

Psychology Today Therapist Finder