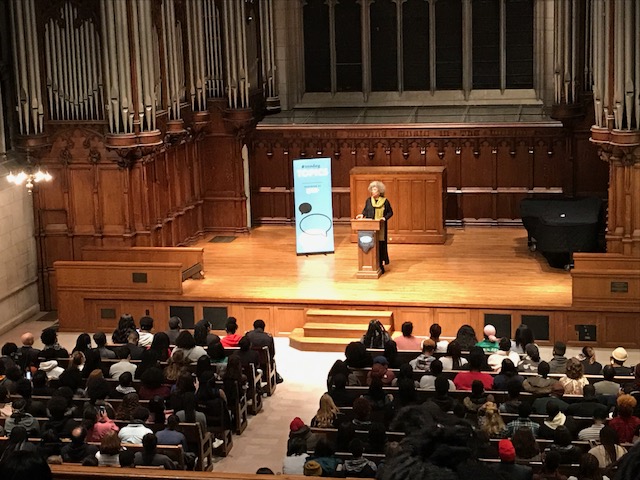

Political activist and author Angela Davis speaks at Washington University’s Graham Chapel

Activist Angela Davis speaks to over 700 students and community members at Washington University’s Graham Chapel.

February 21, 2018

Angela Davis is a 73-year-old political activist, author, and speaker, internationally renowned for her activism in the Civil Rights movement (though she has participated in countless other protests, as well as written several books on their socio-political origins).

I have seen her speak once before, at the 2016 Women’s march in Washington D.C. Her speech then reflected themes of solidarity and community against the ignoble powers of the current presidential administration, as well as addressed the oppression of several marginalized groups.

Davis shared a similar message with over seven hundred St. Louisans.

The event was arranged by WashU’s Student Union — a band of undergraduates concerned with event-planning on campus. After hours of waiting in the biting cold, WashU undergraduate students were admitted into the Graham Chapel, a large venue located on the Danforth campus. Once all undergraduates were seated, WashU graduate students were invited inside, then the general public. In total, 713 people were seated inside the Graham Chapel.

Once settled, people around me took up a hum of excitement, one that only increased as a SU spokeswoman opened the evening with a description of Angela Davis’ exploits. Every camera in the room was poised, every breath held — the entire crowd seemed to quake with anticipation. We were not made to wait long. As soon as 7:00 p.m. struck, a scarf-wrapped woman sporting a familiar afro approached the podium.

The crowd exploded with applause, but through it rose the sultry voice of Angela Davis, with a remark of: “Who could have ever predicted that no more than a year ago a man could be elected to the presidency who, by his own words, liked to sexually molest women?”

The tone of the evening’s speech was effectively set: sexual harassment. Davis began with an expansion of President Donald Trump’s sex crimes, as articulated by his taped comments.

“With these few words,” Davis said, “[Trump] sums up the objectification and sexualization of women linked to patriarchal ideology…this is what Harvey Weinstein thought; Bill Cosby.”

The latter’s name was almost whispered, Davis’ way of bringing emphasis to the fact that not all sexual predators were white anglo-Saxon males, as she later explained.

Larry Nassar too was included in her condemnation, through Davis’ reading of a statement given by Olympic champion Aly Raisman at Nassar’s trial:

“You do realize now the women you so heartlessly abused over such a long period of time are now a force, and you are nothing.”

From this, Davis moved to the topic of movements, and how often they are dismissed by the illusion of individual courage.

“It is to a certain extent,” she said, “but it’s also about movements, and a sense of community, and a sense of productivity…I want us to critique the individualistic mindset that causes us to ignore the origin.”

Because, as Davis explained, the obscurity of movements applies both ways: movements against oppression are often dismantled by feelings of singleness, and movements of oppression (or “institutional underpinnings”) are ignored and attributed to a single individual.

As Davis put it, “How will imprisoning the man eradicate the phenomenon?”

After being imprisoned herself, Davis concluded that the “state”, or government, were the true perpetrators of abuse, and explained that any discussion of removing women from the military should be preceded by a critique of the military itself, just as any withholding of marriage rights from same-sex couples should be preceded by a critique of marriage.

“[Dr. Martin Luther King] pointed out that you cannot see justice as something that should be awarded to particular groups and particular communities…particular struggles,” Davis said, “you can’t say ‘I’m opposed to racism,’ but I don’t think people of the same gender can love each other…justice is indivisible.”

After this, Davis opened the floor for questions; instantly a hundred hands shot into the air. How to make women’s marches more inclusive, how sexual violence is related to Palestine — but it was the last question that truly seemed to impassion the crowd. What, in all this, is the role of the artist?

“Artists give people the inspiration to seek answers — ones that are not yet apparent,” Davis replied, after embracing the Student Union member who’d asked the question. “Art leads the way, art is a beacon…the only way to imagine a world without violence is to conceptualize through the imagination of artists.”