The Handmaid’s Tale’s Margaret Atwood Visits the Sheldon

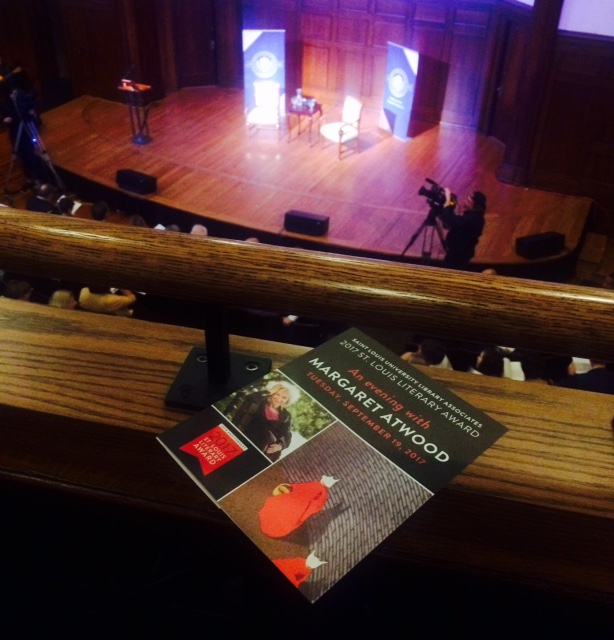

The Sheldon minutes before Margaret Atwood strode onto the stage.

October 3, 2017

The lights dimmed. I squirmed in my seat. In front of me, past rows and rows of expectant (and predominantly grizzled) heads, was a stage. On the stage were two plush white chairs, a spindly square table between them holding two cups of water and a pitcher. The people around me quieted; I could feel the tension grating the air. An announcer no one was looking at or listening to announced something, and a door on the far side of the stage slowly opened. And onto the stage walked a stooped, gray-haired woman wrapped in in a red scarf. She smiled at us, and there was a split second of awed silence. Then, in unison, we leapt to our feet and applauded madly, me repressing the urge to shriek. Others had no such restraint, but how could they? This was Margaret Atwood.

Perhaps you’ve heard of The Handmaid’s Tale, that one Hulu show everyone is currently obsessing over. Well, that’s actually an adaption of her 1985 novel by the same title, and is probably the most well-known of her novels. Atwood, however, is author to more than thirty-five works of fiction, poetry, and essays, published in over forty countries. In other words, she is a literary legend. On September 19th she came to St. Louis’ Sheldon Concert Hall to claim the 50th St. Louis Literary Award.

Atwood has never been one to shy away from heavy topics. Many, if not all, of her pieces hit upon sensitive and controversial issues such as genetic engineering, ethics in science, politics, sexual rights, climate change and corporate greed. Is is this quality of hers that left me unsurprised when one of the first things she did in her opening words was give us a word of warning.

“A country in which police act as judge, as jury and executioner is a police state,” she said. “…but just and fair laws are administered without discrimination. Please don’t settle for less.”

After uproarious applause, Atwood went on to thank the St. Louis community for her award, and sit in one of the white chairs. A reporter took the other, and began to ask her the audience’s questions. Many of them were, consequently, over The Handmaid’s Tale, but others probed into her writing process, which happened to be my greatest curiosity. Merrily, she described how she made her characters so real, and how she dealt with consistency within longer works and series. However, one question elicited a response so powerful that I wrote it down and underlined it three times.

“Follow your calling, whether you record, dramatize, reflect, or craft beautiful lies.”

This phrase hung over me through the rest of her interview and after, when I purchased my own copy of The Handmaid’s Tale as well as The Penelopiad, another novel of hers. And when I went home and faced the creative works that I had neglected out of spite, impatience, or hopelessness, that I had abandoned because I didn’t think they’d ever amount to anything, I felt hope swell through me. And I began to work on them.

There is a lot we, as artists, can learn from Margaret Atwood. She teaches us to be fearless and unapologetic, but also to allow ourselves to be vulnerable. She encourages us to question our society without restraint but also look into our own values and processes for the answers we seek. Most of all, Atwood reminds us that if you really love something, you must pursue it; her fifty-year career shows us nothing if not this. If you follow your art, it will take you as far as you desire to go.